The temporary’s key findings are:

- Excessive inflation typically harms older households, however the impression varies by retirement standing and wealth.

- Retirees are damage greater than close to retirees as a result of, exterior of Social Safety, their revenue is much less listed to costs and so they maintain much less fixed-rate debt.

- Greater-wealth households – each retirees and close to retirees – are extra protected as a result of they spend money on belongings that develop with inflation.

- Subsequent, the authors will use new survey information to evaluate how older households’ responses to inflation affect these outcomes.

Introduction

In June 2022, U.S. inflation peaked at 8.9 p.c – a dramatically excessive degree after practically three a long time of comparatively secure costs. As a result of inflation has been so low for thus lengthy, the dangers of inflation have been typically missed and up to date historical past doesn’t provide a lot sensible perception on its impression. However a shock of the magnitude simply skilled should absolutely have affected the retirement safety of close to retirees and people already retired.

This temporary, which is the primary of two primarily based on a brand new examine, illustrates the monetary penalties of excessive inflation through the use of financial concept and hypothetical households to hint attainable paths of consumption and wealth beneath completely different macroeconomic eventualities. The findings on this first temporary assume no behavioral response by the households. The second temporary will current outcomes from a brand new survey that explores the extent to which older staff and retirees modified their labor provide, saving, and funding allocation in response to inflation and can incorporate these responses into the state of affairs evaluation.

For this temporary, the dialogue proceeds as follows. The primary part summarizes what we all know up to now in regards to the impression of an inflation shock on family funds. The second part describes the macroeconomic eventualities. The third part presents the outcomes, which present that the magnitude of the impression is dependent upon two offsetting elements: 1) the extent to which revenue and investments maintain tempo with rising costs; and a pair of) the quantity of fixed-rate debt held by the family.

The ultimate part concludes that whereas inflation harms most older households, the dangers differ throughout the age and wealth distribution. Particularly, inflation harms retirees greater than close to retirees as a result of – exterior of Social Safety – retiree revenue is much less listed to costs, and retirees maintain much less fixed-rate debt. Equally, top-wealth households see a smaller discount in monetary belongings than their lower-wealth counterparts as a result of they’re extra closely invested in equities and companies that develop with inflation. However, top-wealth retirees finally find yourself with a much bigger drop in consumption than their lower-wealth counterparts residing off Social Safety.

What We Learn about Inflation and Family Funds

Research of inflation’s impression on retirement safety typically fall into two camps: pre- and post-COVID-19. Previous to the pandemic, america and lots of Western European nations had not seen a serious rise in worth ranges because the late Seventies and early Eighties. Thus, researchers on this query used statistical evaluation to narrate small modifications in inflation and rates of interest in the course of the Nineteen Nineties and 2000s to the actual worth of family revenue, belongings, and debt. Provided that the inflation fluctuations throughout this era had been very small, it’s tough to extrapolate these outcomes to 2022. Nonetheless, the pre-pandemic literature confirmed a key perception: that inflation impacts households in a different way primarily based on the precise sources of their revenue, the allocation of their belongings, and their publicity to fixed-rate mortgage debt.

On the revenue facet, households approaching retirement face the chance that labor earnings don’t maintain tempo with rising costs. Since wages and salaries are sometimes negotiated on a set schedule (sometimes as soon as per yr), earnings are likely to lag inflation. And unemployment poses a big threat if the Federal Reserve’s response to inflation triggers a recession. Equally, many retirees nonetheless depend on outlined profit (DB) pensions, which regularly don’t maintain tempo with inflation (though these plans are more and more uncommon for personal sector staff). On a extra optimistic notice, most retirees additionally obtain absolutely inflation-indexed revenue from Social Safety.

Concerning wealth, the direct impression of inflation is dependent upon the family’s portfolio and the character of the shock. For instance, monetary fashions predict that bonds and different fixed-income holdings endure from sudden worth will increase. Equities fare higher, as long as the Federal Reserve avoids a recession. And whereas home costs rise with inflation, this development could also be offset by shrinking demand if rising rates of interest make it tougher for potential consumers to take out a mortgage. However, households that already maintain fixed-rate mortgage debt profit from inflation as a result of the month-to-month mortgage fee stays fixed whilst family revenue rises with costs.

Though the present analysis is useful for understanding inflation’s impression on retirement, many questions stay. As an illustration: how weak had been older households to the latest inflation shock, given their revenue, funding allocation, and debt holdings? Have been sure households extra weak than others?

How Weak Are Older Households to an Inflation Shock? A Situation Evaluation

As a result of it’s exhausting to evaluate the impression of at this time’s inflation shock from previous expertise and since inflation continues to be a priority, we flip to state of affairs evaluation. This method makes use of financial concept to mannequin the funds of six hypothetical households – of various ages and wealth ranges – beneath a spread of attainable macroeconomic situations.

Earlier than diving into the evaluation, the next dialogue defines the metrics used to evaluate inflation’s impression on retirement safety, introduces the hypothetical households featured in our illustration, and lays out the macroeconomic eventualities.

How Do We Measure Inflation’s Impression on Retirement Safety?

Intuitively, the quantity of non-housing items and providers that households can eat every year is dependent upon their revenue, prevailing worth ranges, and the extent to which they’ve recurring mounted bills similar to a house mortgage. For working households, this instinct could be expressed with a easy equation:

P * C = I – M – S

The place P denotes the worth of products and providers (we assume a single worth for illustrative functions, such because the CPI-U); C displays the quantity of non-housing items and providers consumed; I represents after-tax revenue; M is the mounted mortgage fee; and S displays any saving that households are doing to construct a inventory of wealth.

The mathematics may be very related for retired households, who obtain revenue (I) from exterior sources – similar to Social Safety or an employer pension – and likewise fund consumption by drawing down their inventory of wealth:

P * C = I + dW – M

The place (d) represents the drawdown price of wealth (W). From one yr to the subsequent, inflation impacts the amount consumed (C) straight by the worth degree (P) and not directly by the expansion of revenue and wealth.

Therefore, our state of affairs evaluation focuses on two metrics. First, we take a look at the actual change in present consumption (C) from the start of our evaluation interval to the top. Second, we additionally think about potential future consumption by evaluating the inventory of family wealth on the finish of the interval. Because the final aim of this train is to grasp the impression of latest inflation, we mannequin consumption and wealth from 2021 to 2025, with all values expressed in 2021 {dollars}.

A Monetary Profile of Older Households

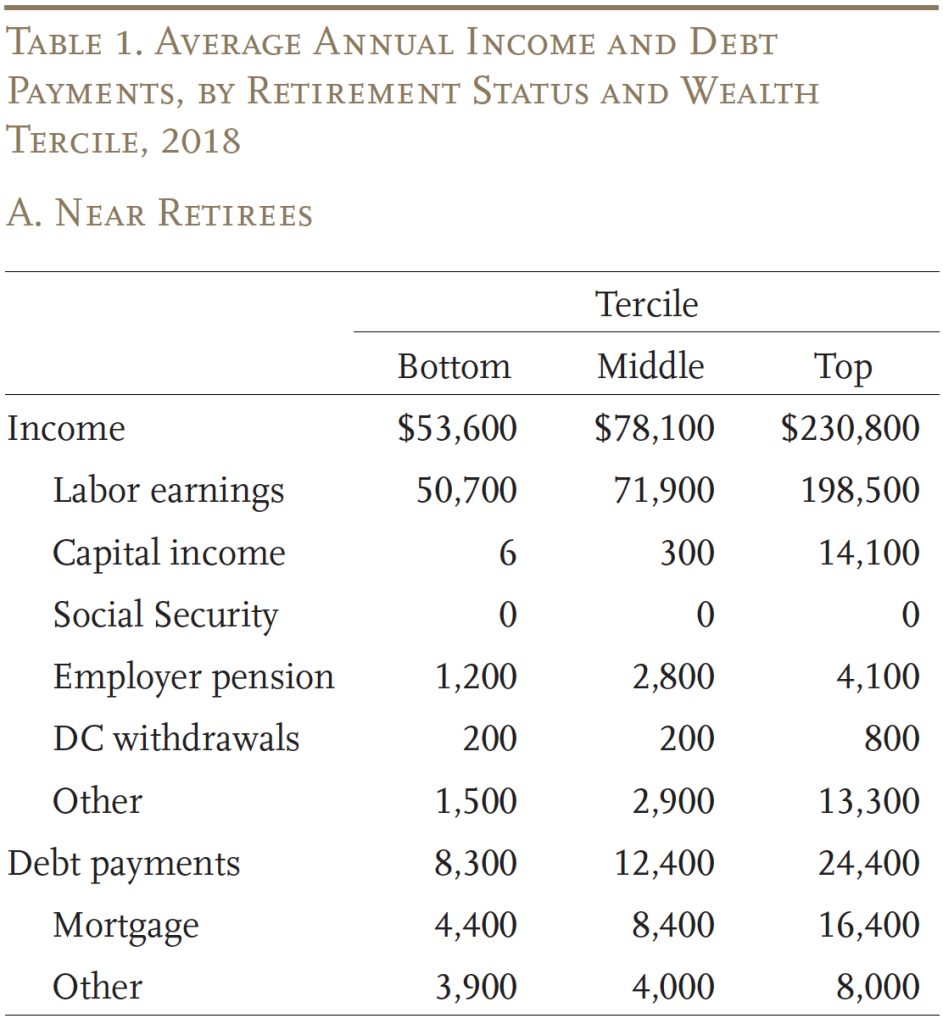

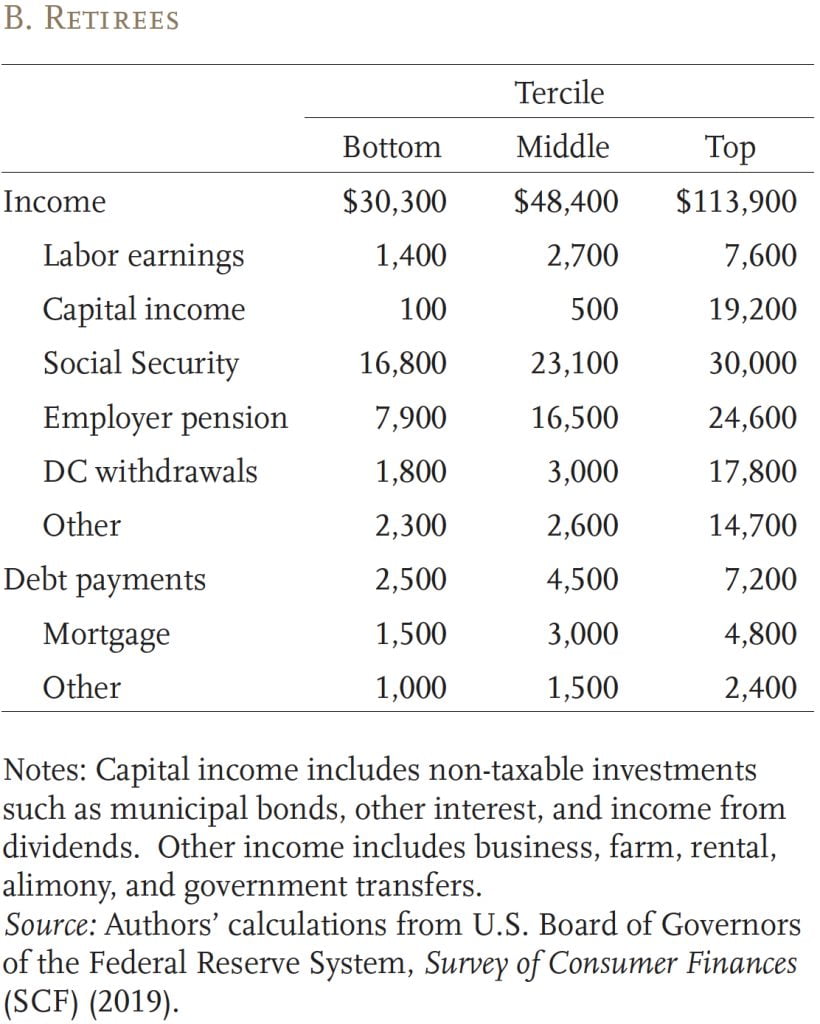

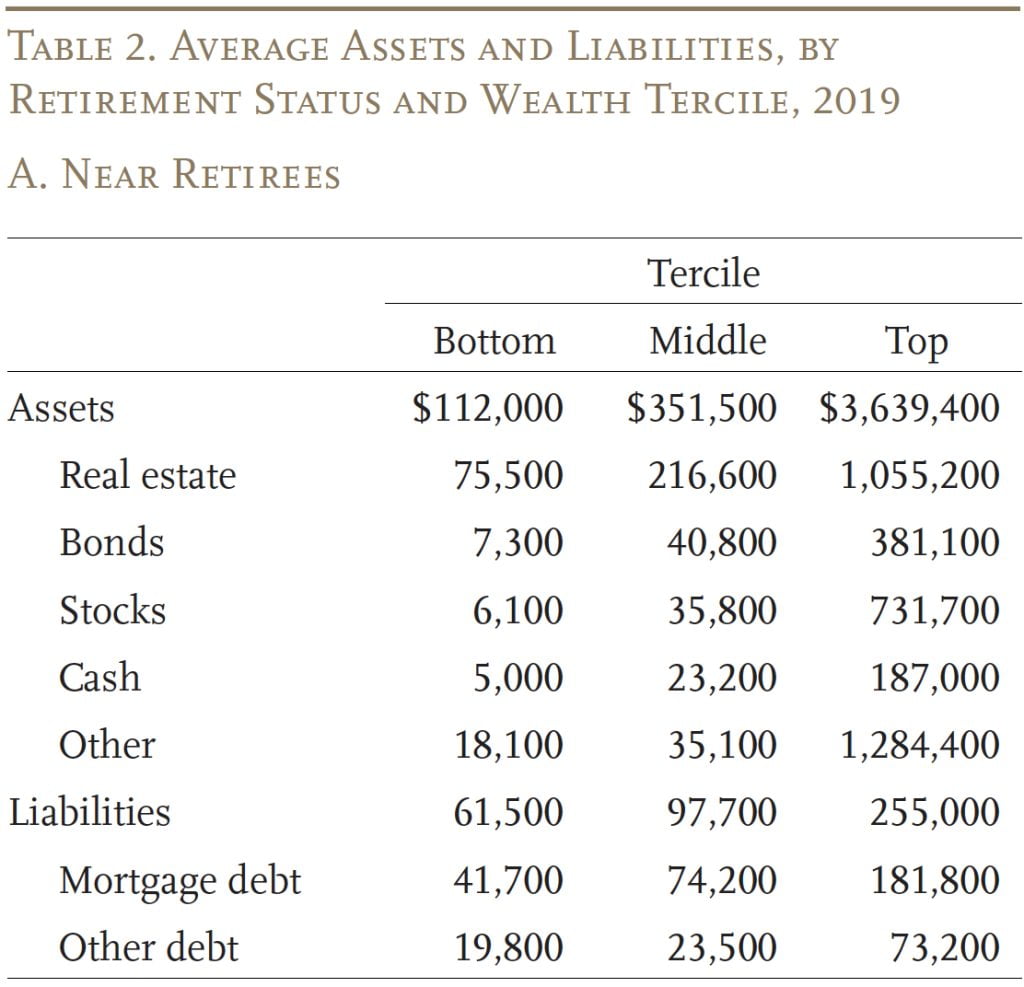

The evaluation considers two teams of hypothetical households whose beginning ranges of revenue and wealth are designed to mirror precise households within the 2019 Survey of Shopper Funds (SCF):

- Close to retirees: for households on this group, the survey-designated “family head” is age 55 to 61 in 2021 and employed full-time. Sixty-two p.c of those households are married, and we stipulate that the partner will not be but receiving Social Safety or pension revenue. In follow, many of the spouses are employed.

- Retirees: households on this group have a head age 62 or over. Each the pinnacle and partner self-identify as retired (46 p.c of those households are married); and the family receives Social Safety revenue.

Desk 1 reveals the parts underlying consumption for households close to and in retirement, by wealth tercile. A lot of the close to retirees have few sources of revenue past labor earnings. These within the high wealth tercile even have funding revenue and revenue from “different” sources similar to companies. Moreover, a modest variety of working households already obtain an employer pension. Importantly, the typical family should spend a portion of its revenue on debt obligations, significantly mortgage funds.

Retirees, in the meantime, obtain most of their revenue from Social Safety and DB pensions. These within the high wealth tercile additionally make vital withdrawals from their outlined contribution (DC) plans (which embrace IRAs) and have notable revenue from capital and “different” sources. Retirees are a lot much less prone to be making mortgage funds than close to retirees.

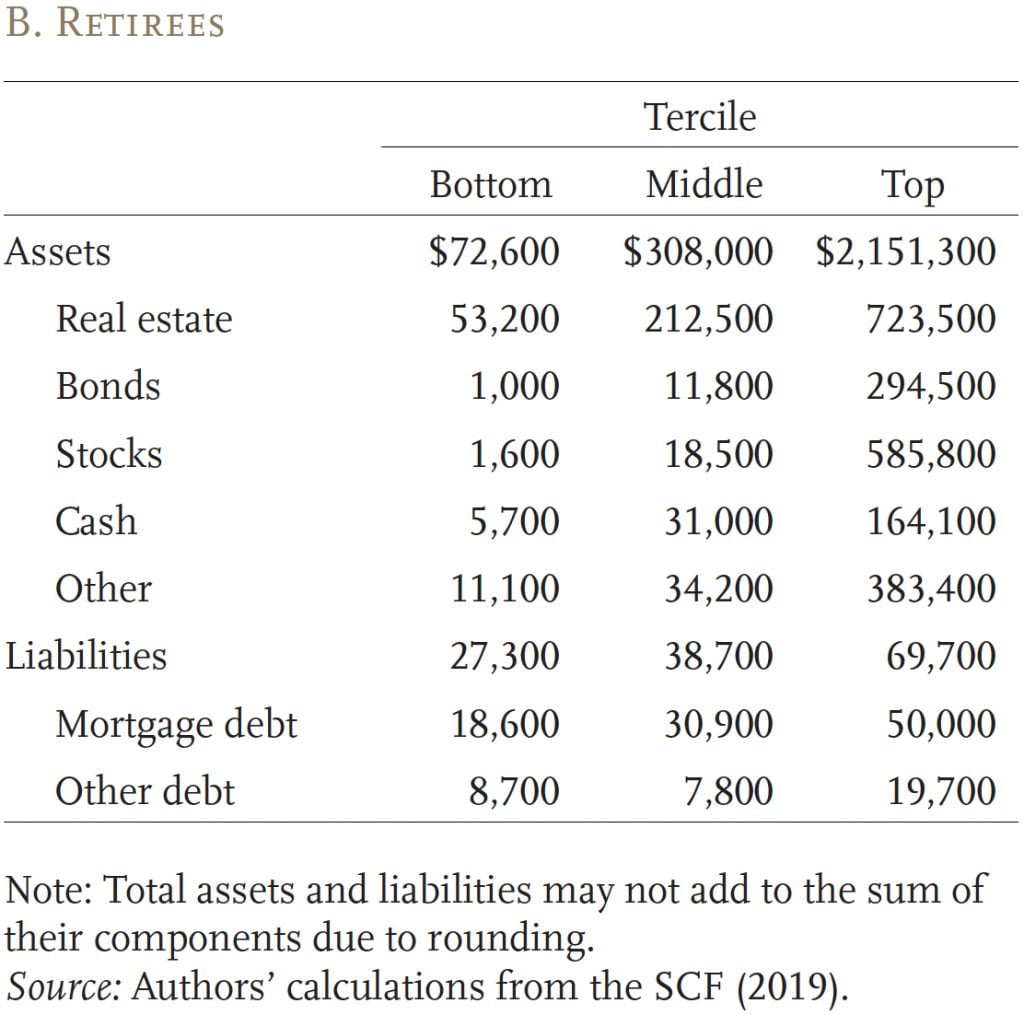

Equally, Desk 2 reveals the parts of wealth by retirement standing and wealth tercile. Housing is the first asset for all households. Nonetheless, these within the high tercile even have vital non-housing wealth within the type of inventory and bond holdings (primarily by DC plans), money (which incorporates certificates of deposit), and “different” belongings (together with companies, annuities, autos, and life insurance coverage). On the liabilities facet of the stability sheet, most households have mortgage debt, though – as famous earlier – this debt is much less vital for wealthier households and retirees.

4 Macroeconomic Situations

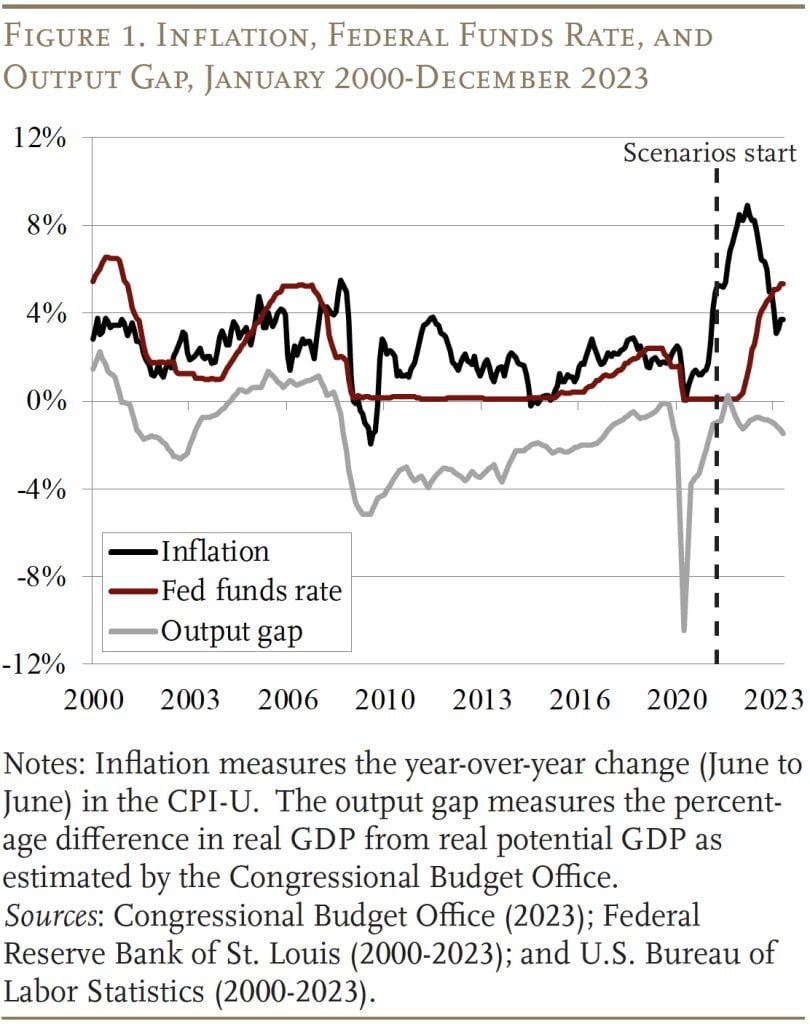

The following step is to find out how inflation impacts the varied parts of revenue and wealth. Our evaluation runs from January 2021 by December 2025. Inflation and rates of interest had been nonetheless low initially of 2021, reflecting a protracted interval of free financial coverage (see Determine 1). Though the economic system had largely recovered from the temporary, however extreme, pandemic recession, the output hole (precise versus potential GDP) was nonetheless damaging.

Inflation can have completely different results relying on the Fed’s coverage response. Because of this, we think about 4 hypothetical eventualities:

No inflation. On this baseline state of affairs, the economic system step by step emerges from the lengthy interval of below-potential development and achieves zero output hole by December 2025. To take care of goal inflation of two p.c with no output hole, the Fed incrementally raises rates of interest to 4 p.c (2 p.c above inflation) by December 2025.

Everlasting shock. On this (fairly unrealistic) state of affairs, the “no inflation” state of affairs is modified in order that inflation all of a sudden spikes at 4 p.c in Might 2021 – as was really the case – and stays at that degree thereafter. Importantly, beneath this state of affairs, the Fed accepts the upper price of inflation as its new goal, and steadily raises the Federal Funds Charge to six p.c to take care of 4-percent inflation and shut the output hole by December 2025.

Gentle touchdown. This third state of affairs considers a extra sensible trajectory for the economic system. Inflation takes off in Might 2021 and the Fed successfully makes use of financial coverage to succeed in its goal of two p.c with no output hole by December 2025 – with out triggering a recession. Particularly, this state of affairs mimics precise macroeconomic situations from 2021 to 2023 – inflation climbing to 9 p.c, a leap within the Federal Funds Charge to over 5 p.c, and a subsequent decline in inflation to only over 3 p.c – after which tasks a easy path ahead to 2-percent inflation, a closing of the output hole, and a 4-percent Federal Funds Charge by December 2025.

Recession. The final state of affairs envisions a recession following aggressive Fed coverage to tamp down inflation. As within the “tender touchdown,” this state of affairs mimics precise macroeconomic situations from 2021 to 2023. However, fairly than a easy return to regular by 2025, inflation begins to rise once more in 2024. The Fed responds by aggressively elevating rates of interest with the Federal Funds Charge peaking at 8 p.c in January 2025. Finally, such a excessive price triggers a recession (about half as extreme because the Nice Recession) and an instantaneous downward development in inflation. Realizing the pricey results of overly aggressive coverage, the Fed shortly brings charges again down; nonetheless, the economic system doesn’t absolutely get better by the top of the evaluation interval.

Conceptually, the primary state of affairs represents a benchmark in opposition to which to measure the general impression of inflation. The following two eventualities present how inflation impacts retirement safety with out the confounding affect of a recession; and the final state of affairs reveals the mixed results of inflation plus a recession.

Projecting Revenue and Wealth Below Totally different Situations

For example the impression of inflation on consumption and wealth, we should make assumptions about how various kinds of revenue and belongings evolve in our macroeconomic eventualities between 2021 and 2025.

- Wages: Matching the standard expertise of staff over age 50, the primary three eventualities assume that wages lag inflation by one yr with no productiveness development. Within the final state of affairs (“recession”), wages lag inflation till the recession happens, after which they freeze.

- Social Safety: Social Safety advantages are absolutely listed for inflation.

- DB pensions: The evaluation assumes that personal DB plans don’t present cost-of-living (COLA) changes, whereas authorities plans grant a COLA equal to the CPI as much as a cap of three p.c.

- Capital and different revenue: Capital revenue is projected to develop with GDP. Different revenue consists of enterprise, farm, and rental revenue – that are presumed to develop with GDP – and alimony and authorities transfers – which stay at present ranges.

- Saving price for working households: Based mostly on information within the 2019 SCF, the evaluation assumes that 34, 64, and 73 p.c of working households within the backside, center, and high terciles, respectively, take part in a DC plan. Equally, wealthier households contribute a bigger proportion of their annual labor earnings to their DC plan.

- Drawdown price for retired households: A rising literature means that households use guidelines of thumb – such because the 4-percent rule or the Required Minimal Distribution (RMD) schedule – to withdraw a set proportion of their retirement accounts every year. For our baseline evaluation, we assume that retirees take RMDs (that are designed to slowly deplete balances in DC plans over a mean lifespan) in response to the schedule for 2022 tax returns.

- Wealth: Mechanically, the change in wealth from one yr to the subsequent is dependent upon the expansion price of the varied belongings held by the family, the share of the portfolio allotted to every asset class, and the decline in debt excellent.

Outcomes of the Situation Evaluation

Finally, we’re occupied with two outcomes – the cumulative change in actual consumption from 2021 to 2025 and wealth in 2025 – for 2 family sorts – close to retirees and retirees – throughout 4 macroeconomic eventualities. All through, we’re aware that, in the actual world, different occasions that additionally affected family funds coincided with inflation. To keep away from evaluating our illustration to real-world outcomes, we current all outcomes relative to the baseline state of affairs of no inflation.

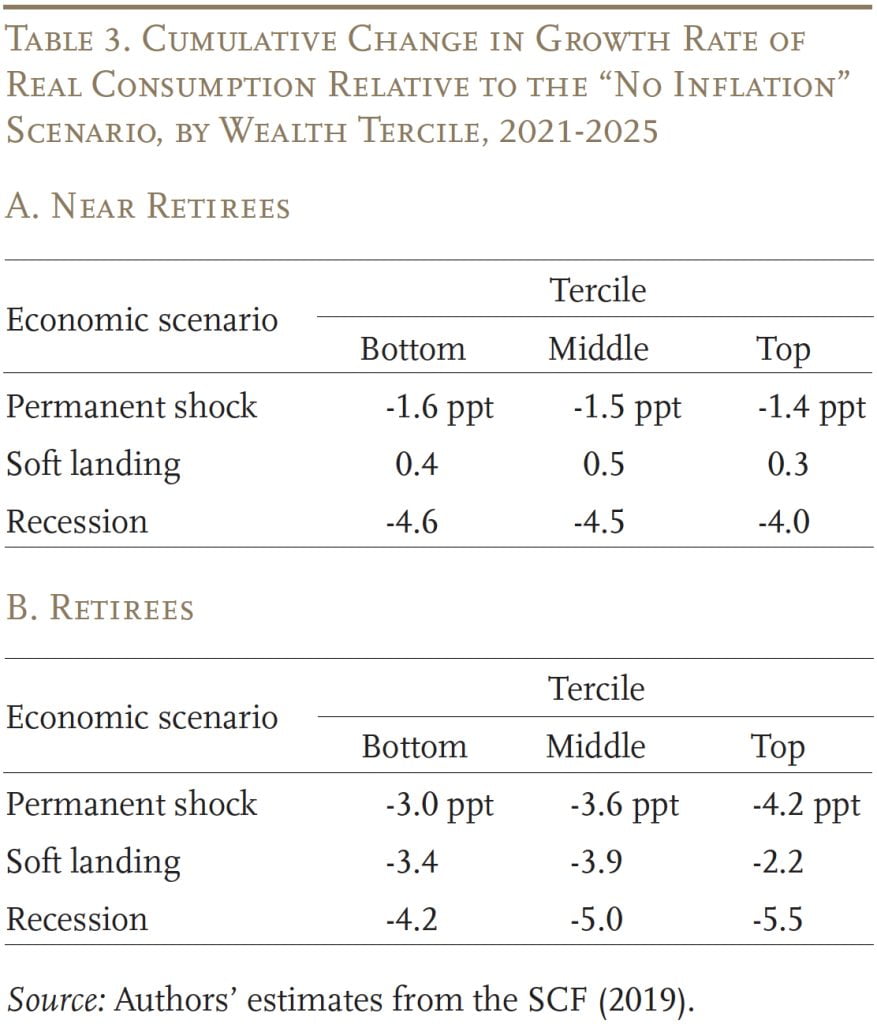

Desk 3 reveals the distinction within the development price of actual consumption throughout eventualities. Two factors stand out. First, close to retirees expertise a smaller decline in consumption than retirees, even having fun with actual consumption features within the “tender touchdown” state of affairs. This consequence is as a result of decline in the actual worth of mortgage funds relative to earnings. Retirees have much less erosion of actual debt, and sometimes additionally lose actual revenue as a result of employer pension advantages are solely partially listed to inflation.

Second, the impression of inflation varies throughout the wealth distribution. Close to retirees within the high wealth tercile typically fare higher than same-age households with fewer sources as a result of they derive extra of their revenue from companies which have actual development. Conversely, retirees within the backside wealth tercile sometimes fare finest as a result of they’re extra reliant on Social Safety, which in our mannequin is listed for inflation with no lag.

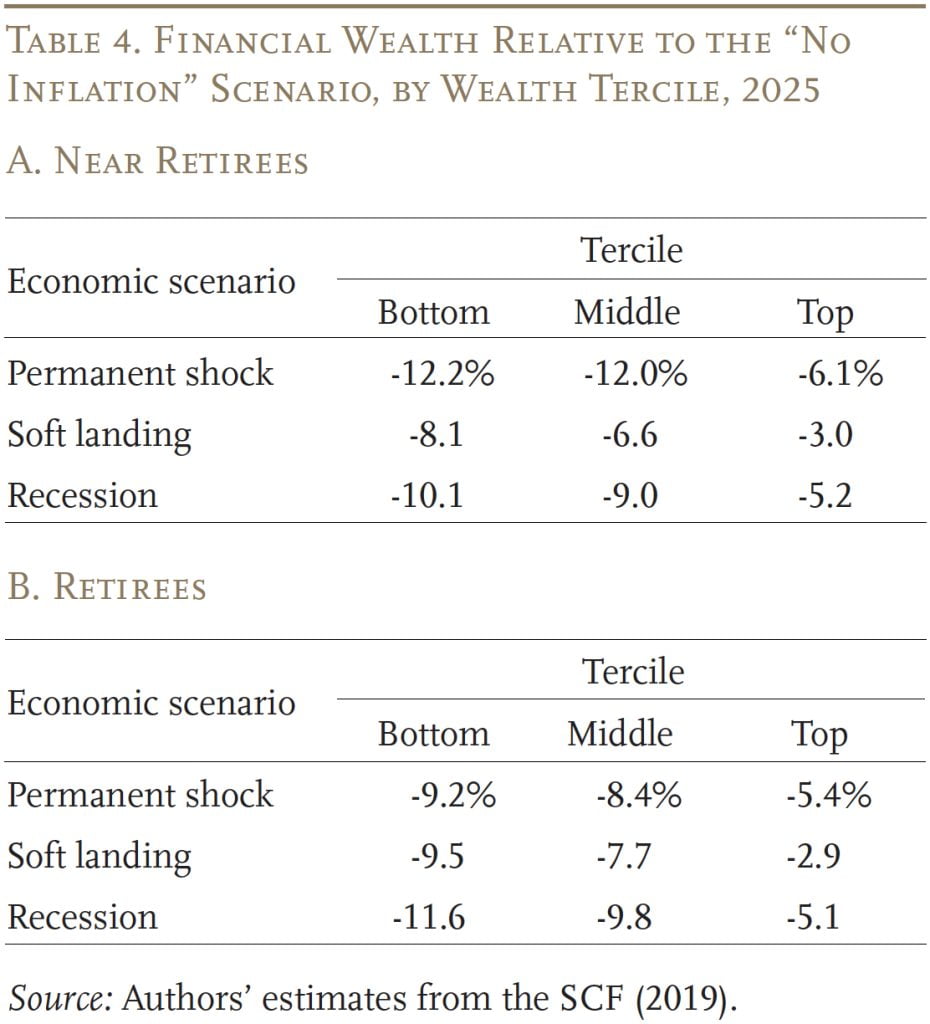

Turning now to monetary (non-housing) wealth in 2025, we see that inflation has an unambiguous damaging impression (see Desk 4). High-wealth households, nonetheless, all the time lose lower than their lower-wealth counterparts, as a result of they make investments extra in equities, companies, and different belongings that develop with inflation.

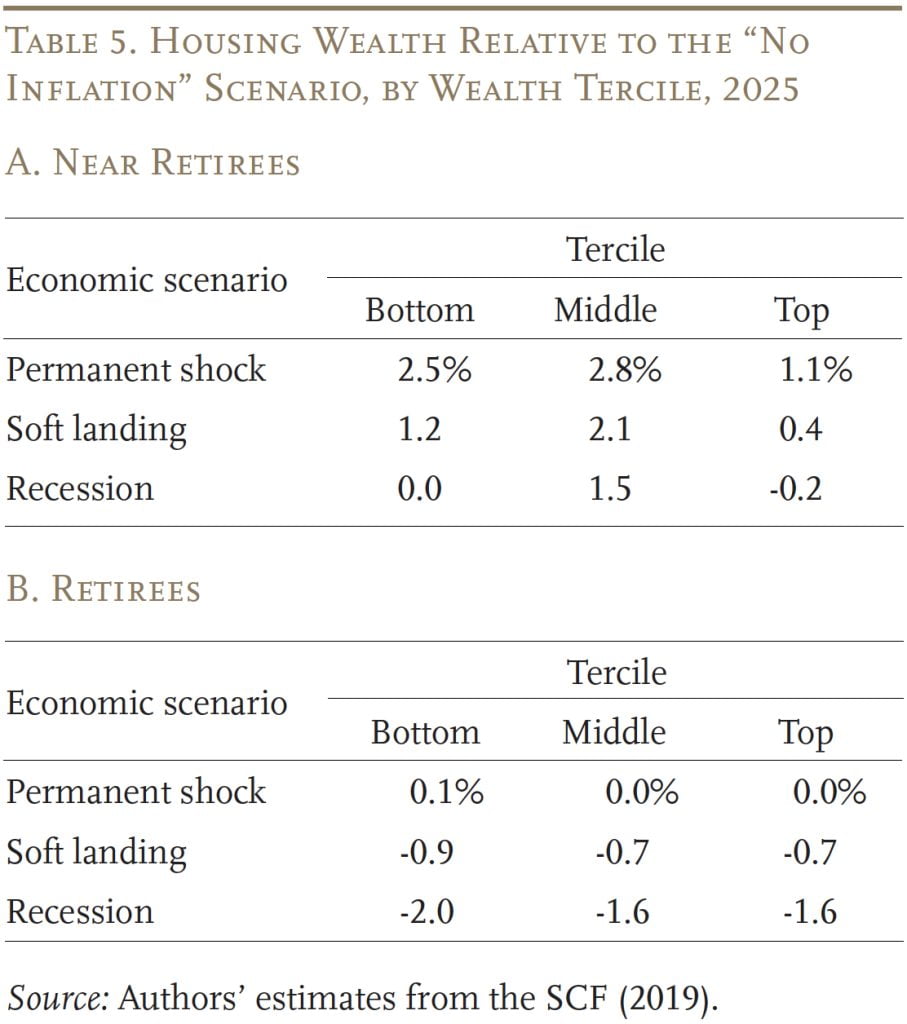

Desk 5 illustrates the impression of inflation on housing wealth in 2025, relative to the “no inflation” state of affairs. In contrast to monetary wealth, inflation doesn’t have a lot impression on housing wealth. On the one hand, residence costs decline as rising actual long-term rates of interest weaken demand; however, inflation erodes the actual burden of mortgage debt. For this latter cause, close to retirees usually come out barely forward of retirees as a result of they extra prone to nonetheless be paying down their mortgage.

In abstract, most older households lose actual consumption and wealth after an inflation shock. The magnitude of the loss is dependent upon the character of the shock, the actual development of revenue and belongings, and the family’s publicity to fixed-rate debt.

Conclusion

Older households have simply had a pointy reminder that inflation might not be secure all through retirement. Experiencing a bout of excessive inflation later in life is usually dangerous to monetary well-being, however, as anticipated, the impression varies relying on the family’s particular monetary profile: the extent to which revenue and belongings develop with (or lag) inflation, and the quantity of debt excellent.

At this level, the tender touchdown state of affairs appears most consultant of the present state of affairs. Close to retirees on this state of affairs seem to achieve in consumption and housing wealth relative to a no-inflation state of affairs primarily as a result of decline in the actual worth of mortgages. In distinction, regardless of absolutely inflation-adjusted Social Safety advantages, retirees lose out resulting from having much less fixed-rate debt and likewise a decline in actual revenue as employer pension advantages are solely partially listed to inflation.

This temporary, nonetheless, is just a primary take a look at the impression of inflation on older households. A key query is how close to retirees and retirees react to inflation and the way their actions have an effect on their consumption over the interval and their wealth on the finish. This matter will likely be addressed in our second temporary.

References

Adam, Klaus and Panagiota Tzamourani. 2016. “Distributional Penalties of Asset Worth Inflation within the Euro Space.” European Financial Overview 89: 172-192.

Albanesi, Stefania. 2007. “Inflation and Inequality.” Journal of Financial Economics 54(4): 1088-1114.

Aubry, Jean-Pierre and Laura D. Quinby. 2024. “What Dangers Do Close to Retirees and Retirees Face from Inflation, and How Do They React?” Particular Report. Chestnut Hill, MA: Heart for Retirement Analysis at Boston School.

Auclert, Adrien. 2019. “Financial Coverage and the Redistribution Channel.” American Financial Overview 109(6): 2333-2367.

Bach, G. L. and James B. Stephenson. 1974. “Inflation and the Redistribution of Wealth.” Overview of Economics and Statistics 56(1): 1-13.

Bartscher, Alina Okay., Moritz Schularick, Moritz Kuhn, and Paul Wachtel. 2022. “Financial Coverage and Racial Inequality.” Brookings Papers on Financial Exercise (Spring): 1-63.

Bernanke, Ben S. 2015. “The Taylor Rule: A Benchmark for Financial Coverage?” Commentary. Washington, DC: Brookings Establishment.

Brown, Jeffrey R., James M. Poterba, and David P. Richardson. 2023. “Traits in Retirement and Retirement Revenue Selections by TIAA Individuals: 2000-2018.” Journal of Pension Economics and Finance.

Cieslak, Anna and Carolin Pflueger. 2023. “Inflation and Asset Returns.” Working Paper 31124. Cambridge, MA: Nationwide Bureau of Financial Analysis.

Congressional Finances Workplace. 2023. “The 2023 Lengthy-Time period Finances Outlook: Information Complement.” Washington, DC.

Crawford, Ian and Zoe Oldfield. 2002. “Distributional Facets of Inflation.” London, UK: The Institute for Fiscal Research.

Del Canto, Felipe N., John R. Grisby, Eric Qian, and Conor Walsh. 2023. “Are Inflationary Shocks Regressive? A Possible Set Method.” Working Paper 30982. Cambridge, MA: Nationwide Bureau of Financial Analysis.

Doepke, Matthias and Martin Schneider. 2006a. “Mixture Implications of Wealth Redistribution: The Case of Inflation.” Journal of the European Financial Affiliation 4(2-3): 493-502.

Doepke, Matthias and Martin Schneider. 2006b. “Inflation as a Redistribution Shock: Results on Aggregates and Welfare.” Working Paper 12319. Cambridge, MA: Nationwide Bureau of Financial Analysis.

Doepke, Matthias and Martin Schneider. 2006c. “Inflation and the Redistribution of Nominal Wealth.” Journal of Political Financial system 114(6): 1069-1097.

Erosa, Andres and Gustavo Ventura. 2002. “On Inflation as Regressive Consumption Tax.” Journal of Financial Economics 49: 761-795.

Federal Reserve Financial institution of St. Louis. 2000-2023. “Federal Funds Efficient Charge.” St. Louis, MO.

Glaeser, Edward L., Joshua D. Gottlieb, Joseph Gyourko. 2010. “Can Low-cost Credit score Clarify the Housing Growth?” In Housing and the Monetary Disaster, edited by Edward L. Glaeser and Todd Sinai, 301-360. Chicago, IL: College of Chicago Press.

Gurer, Eren and Alfons Weichenrieder. 2020. “Professional-rich Inflation in Europe: Implications for the Measurement of Inequality.” German Financial Overview 21(1): 107-138.

Hobijn, Bart and David Lagakos. 2005. “Inflation Inequality in america.” Overview of Revenue and Wealth 51(4): 581-606.

Hottman, Colin J. and Ryan Monarch. 2020. “A Matter of Style: Estimating Import Worth Inflation throughout US Revenue Teams.” Journal of Worldwide Economics 127(103382): 1-16.

Inner Income Service. 2022. Distributions from Particular person Retirement Preparations (IRAs). Publication 590-B. Washington, DC.

Jaravel, Xavier. 2021. “Inflation Inequality: Measurement, Causes, and Coverage Implications.” Annual Overview of Economics 13: 599-629.

Kaplan, Greg and Sam Schulhofer-Wohl. 2017. “Inflation on the Family Stage.” Journal of Financial Economics 91: 19-38.

Lauper, Christoph and Giacomo Mangiante. 2021. “Financial Coverage Shocks and Inflation Inequality.” Working Paper.

Lee, Munseob, Claudia Macaluso, and Felipe Schwartzman. 2021. “Minority Unemployment, Inflation, and Financial Coverage.” Working Paper. Minneapolis, MN: Federal Reserve Financial institution of Minneapolis.

McGranahan, Leslie and Anna Paulson. 2005. “Developing the Chicago Fed Revenue Based mostly Financial Index-Shopper Worth Index: Inflation Experiences by Demographic Group: 1983-2005.” Working Paper. Chicago, IL: Federal Reserve Financial institution of Chicago.

McKay, Alisdair and Christian Okay. Wolf. 2023. “Financial Coverage and Inequality.” Journal of Financial Views 37(1): 121-144.

Munnell, Alicia H., Gal Wettstein, and Wenliang Hou. 2020. “How Greatest to Annuitize Outlined Contribution Belongings?” Journal of Danger and Insurance coverage 89(1): 211-235.

Munnell, Alicia H., Jean-Pierre Aubry, and Mark Cafarelli. 2014. “COLA Cuts in State/Native Pensions.” Concern in Transient 38. Chestnut Hill, MA: Heart for Retirement Analysis at Boston School.

Orchard, Jacob. 2022. “Cyclical Demand Shifts and Price of Dwelling Inequality.” Working Paper.

U.S. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Survey of Shopper Funds, 2019. Washington, DC.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2000-2023. “Shopper Worth Index.” Washington, DC.

Wolff, Edward N. 2023. “Is There Actually an Inflation Tax? Not for the Center Class and the Extremely-Rich.” Working Paper 31775. Cambridge, MA: Nationwide Bureau of Financial Analysis.

Yang, Yucheng. 2022. “Redistributive Inflation and Optimum Financial Coverage.” Working Paper.